Where "radical candor" is wrong for feedback

How to give and receive candid feedback without being a radical.

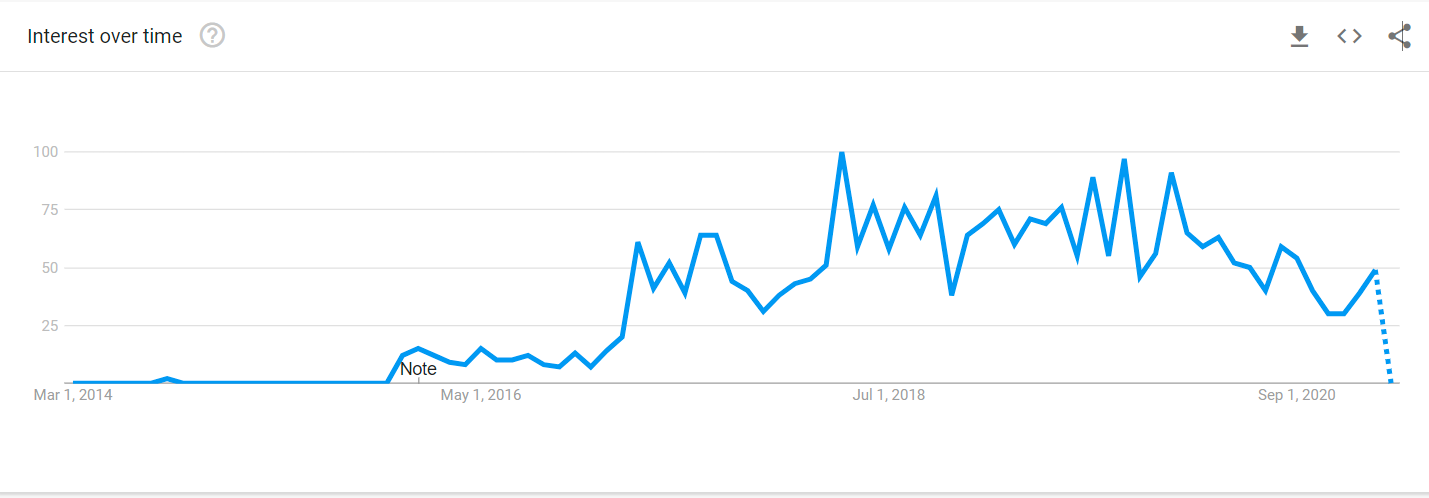

Over the last 3 years, there’s been an increased interest in “radical candor” and it’s variations: brutal honesty, radical transparency, and radical honesty.

The concept isn’t new, as philosopher Immanuel Kant discussed the duty of truthfulness in “On a Supposed Right to Tell Lies from Benevolent Motives” in 1797. However, I always had troubles with the adjective “radical”. Must we be an extremists when it comes to candor, especially at work?

What is feedback?

In casual conversation, feedback is the opinions of one person about another person’s action, work, decisions, etc.

These “opinions” occur when person A does something that causes person B to have a reaction, which is shared back to person A as feedback, a cause and effect loop.

Why giving good feedback is hard.

There are several reasons:

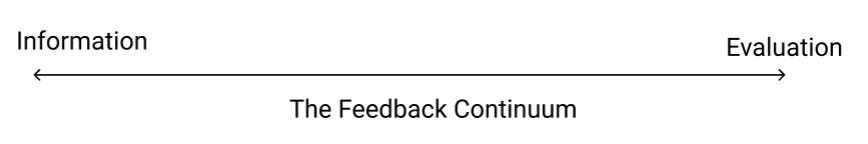

Feedback resides on a continuum between information and evaluation.

Information is data: “The chicken dish is raw.” or “Your action made me angry”.

Evaluation focuses on “determination of a subject's merit, worth and significance”. “Serving raw chicken is bad.” or “People who are angry make poor coworkers.”

Most feedback we give is both informative and evaluative: “The restaurant is bad (evaluation) because the dish had undercooked, raw chicken (information).” This combination makes it difficult for recipients to separate data from judgement. Second, we, as recipients over index on the evaluation (i.e., bad). Third, the evaluation can be subjective, which the recipient can disagree with, making it easy to also dismiss the information part of the feedback.

Giving evaluation feedback is easier than information feedback.

Say I look at a design:

It’s less work mentally to give a judgement, “This looks great!”, than to articulate information about what aspect of the design that’s great “the separation of the CTA for “Log in” and “Get started — it’s free” in the top navigation while keeping the colors to a minimal, and changes only when you scroll down.

But judgements like “good/like” don’t provide substantive information for the recipient to make changes in the cause and effect loop. PMs know from conducting user interviews how unhelpful positive, evaluation feedback can be. It can feel good, but that’s it.

Furthermore, PMs tend to gravitate towards giving evaluation feedback because making judgements with incomplete information is part of the job. This learned behavior is reinforced and carries over.

It’s hard to take into consideration of recipient’s goal

“Good” feedback isn’t solely determined by the person giving the feedback. The recipient’s goals, effort made, assumptions about the purpose of feedback, prior feedback experience, as well as their emotional response are all elements that influence whether the feedback will be effective. Thus, the person giving the feedback has to find the sweet spot. Not easy.

Why being “radical” is unnecessary.

Because giving “good” feedback is difficult, many people give poor feedback. Recipients who receive poor feedback find it unhelpful or become defensive and argumentative. A negative cause and effect loops is created. Over time, people are more hesitant to give feedback and recipients are hesitant to seek feedback.

This is where the “radical” argument starts. To restart the loop, let’s start with “It’s better to say it as-is, even if it isn’t perfect. At least, I’m honest and the recipient can take it as they see fit.” It’s intention is good, but it has resulted in two problems.

First, some people have “weaponized” candor to be unnecessarily harsh because they think recipients “need to hear the truth”. I was on a discussion recently where a VC proudly told the story of how the best honest advice she received early in her career, was when another VC said, “This idea is dumb because you aren’t fat, and don’t have founder-fit to for this business.” It was lauded by the recipient as “tough love”, saving time so she didn’t pursue an idea (plus size clothing brand) that would have been unsuccessful.

But I think candor can be achieved without being unnecessarily harsh by giving informational feedback (e.g., “I see founders who have succeeded with DTC brands. They personally embody the problem and product. Here are examples: company A, B, C. You do not fit this. Thus, my judgement is you won’t succeed because X, Y, Z.”).

Secondly, “radical candor”, even as the writer Kim Scott says, requires a level of personal “care” or love that most work environments don’t provide. There’s a reason “tough love” is usually reserved to describe parents, because it’s the “unconditional” part. What occurs too frequently at work is people champion the “direct” part without the “love” part. “Truth is vital, but without love, it is unbearable.” And while I agree, people who have built such strong relationships at work can practice “radical candor”, what about the cases when you need to give feedback to someone (e.g., peers, bosses) and you don’t have such a “loving” relationships?

We don’t need to be either a radical nor silent when it comes to giving and receiving feedback. It’s great to develop deep relationships where you can practice “tough love” at work, but in many cases, you need to give direct, candid feedback via practiced informational feedback.

Guide to giving good informational feedback

Ask yourself, what’s your goal in giving feedback? Then, ask the recipient, why are they seeking feedback? When we give feedback, we don’t consider why we’re giving feedback. Nor do we ask, what kind of feedback does the recipient seek. Instead, we say the first things that come to our mind. Define a goal and see if it matches the recipients goal for feedback.

Ask yourself: is it acceptable if the recipient doesn’t take my feedback? One principle I wrote in Running effective 1:1 for managers and reports, is “People managers need to be explicit and understand the difference between instruction and guidance.” This applies for feedback too, whether informative or evaluation. Do you want the person receiving the feedback to do something? Are you okay if the person does nothing afterwards? Too frequently, we mask our instructions or requests as feedback (e.g., “This email is bad. It’s unclear.” -> “I’m instructing you to rewrite and resend the email, keep it to less than 300 words and don’t include any pictures so I can read it on my phone on the go.”)

Be specific or say you don’t know. Ambiguous feedback is often received by the recipient as non-caring at best and confusing at worst. It’s difficult to be specific because it takes more mental work, but good feedback requires specificity. It’s also okay to say, you don’t have any.

Immediacy, but don’t interrupt. Give feedback as soon as the action, work, or event is complete. However, don’t give feedback that will interrupt a performance. That’s because studies show that giving feedback, even informative feedback, when someone is concentrating and focused will cause cognitive overload and impair performance. If you believe action taken is irreversible, you can tell the person you’ll take over. Otherwise, give feedback only after the work is complete.

Use “I would” not “You should”. Directive feedback (e.g., Do ABC) is poorly received. It puts people in the defensive. Instead, use first-person to demonstrate what you would do. (e.g., In this situation, I would do XYZ because ABC).

Tell people your judgement, just label it as judgement. Sometimes, we have an instinctive negative reaction (e.g., dumb, stupid, bad, etc.) You don’t have to hold it in. Instead, tell the person you reacted negatively, but aren’t sure why. Then, walk through your thinking out loud (e.g., “My instinct is negative, but I’m not sure I can explain why. Here, let me try and let’s focus on the information I see.”). This technique allows you to be vocal, label the initial feedback as evaluation, but focus the feedback session on the information.

How to receive feedback

Focus on information, not evaluation. It’s not possible to assume all feedback given will be “good”. When someone gives feedback that is an evaluation of your merit, worth, or value, ask questions to tease out the information feedback. One question you can start, “How would you have done this differently?”

Prime yourself with a learning mindset. It’s difficult to hear negative feedback. Our minds sometimes turn to information feedback “The chicken is raw.” into “I’m a bad cook.” To strengthen your resilience, research shows you can prime yourself by reading articles and seeing how others failed and overcame failure. My go to video:

It’s okay to ignore and redirect feedback. During a job interview, a CEO once gave me feedback that he assessed I lacked self-awareness and a process for tracking feedback. He then gave an example of how his cofounder kept a running list of all the feedback he’s received, crossing them off once he’s made improvements. I was shocked by his feedback because I knew from my own self-reflection and feedback from bosses, coworkers, and direct reports, I did not lack self-awareness and a process. I actually keep a list as well, although it could be better organized. So his information feedback to me was wrong. However, it took me much longer to realize that I lacked a systematic process for practicing interviews and thus likely rambled in my answer to the question. My unclear answer gave the incorrect information. I ignored one type of feedback to focus on another.

Sources

What makes good feedback good? by Berry M. O’Donovan, Birgit den Outer, Margaret Price, Andy Lloyd

Harvard: Feedback vs. evaluation: Getting past the reluctance to deliver negative feedback

Additional Reading