Product Metrics: Defining and picking the right metric for your product.

Understanding the difference between business metrics and product metrics

Metrics. Selecting the correct metric is critical for any product, but finding it can feel like swimming through molasses. We throw around three word acronym like CAC or LTV, add a sprinkle of KPI, mix with some charts, and we’ve created an alphabet soup of WTF. I’ll admit that in this soup, I’ve even confused myself. Thus, let’s learn how metrics tie into strategy, understand the difference between business and product metrics, and look at a framework for picking the right metrics for your product.

What is a metric?

A quantitative measurement.

Why have metrics?

To amalgamate information so we can more easily evaluate, compare, and assess.

Take the metric grade point average (GPA) as an example. It takes all the work a student does, across different classes and performance in those classes and converts it to a single data point (0 - 4.0 in U.S.). With GPA, we can more easily evaluate a student’s performance and compare students against one another. What we lose in fidelity (e.g., two students taking different type of courses), we gain in simplicity and ease of use.

What does metric have to do with strategy?

If you read the above and started nodding in agreement, you’ve fallen into a small trap I’ve laid. Yes, metrics simplify. But a metric by itself doesn’t tell you what you should do. Let’s go back to the GPA example.

If your GPA is 3.5 and another student is 3.6, what would you do? Do you:

study harder in a particular class to ace an exam?

ask your teacher for extra credit assignment?

drop a class that’s difficult to take an easier class where you’d excel with less effort?

do nothing?

Answering “what do you do” depends on your goal and corresponding strategy. What do you want to accomplish with your education and what is your target (e.g., 3.6, 4.0, 3.0, if GPA is a target at all). If your goal is to be eligible for a scholarship and your strategy is taking the easiest classes to obtain >3.8 GPA as stated in the scholarship eligibility rules, you know what you need to do: pick some easier classes. However, if your goals change (e.g., be better at soccer that your brother), your strategy may also change (e.g., entice him to stop practicing with video games), and the metric need to change too.

In summary, the right metric you pick has to be thought of in terms of your goals and strategy.

——————————————————————————————————————

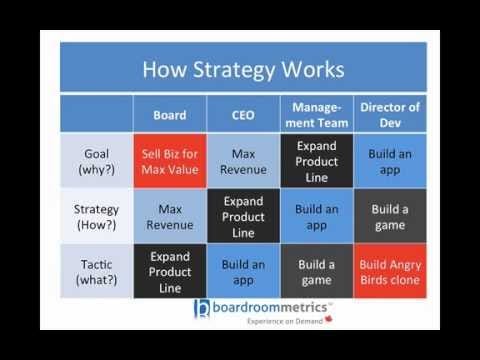

If the example I gave on how metrics are tied to goal and strategy sound simple, why are there so many metrics and why do people get confused? Here’s a picture that I found to help unpack this problem.

If you look at the picture, you’ll see there are different “levels” of goals and strategy. The strategy for one group translates to goals for another. If you’re the PM on a product team building a gaming app and thinking about metrics for your strategy and goal, those metrics are likely different than the metrics the CEO is thinking. This is where I’m going to introduce the concept of business metrics vs. product metrics.

Goals is to business metrics as strategy is to product metrics

Majority of businesses, but especially startups, start with this one goal: maximize profit via growth. All other problems or resulting issues can be masked or solved if growth is satisfied. But what is “growth” and how is it measured? Typically, in one or two ways:

Revenue ($): Net revenue, gross revenue, gross sales, daily/monthly/annual recurring revenue, average order value, life time value

Customers (ppl or clients, which then translate into $): Net users, daily/monthly active users, net accounts

But the problem for product folks is that these business metrics don’t help inform you what ways to change your product. Let’s get to a specific example:

Say the business goal is to max revenue and you’re using the metric gross revenue to track this goal. You have a target of a quarterly revenue of $5MM.

End of the quarter and you find your gross revenue is $4.5MM. So you’ve come up short.

What now ? What action do you take to improve your product?

You see, it isn’t that business metrics aren’t important. I see a lot of product folks get confused, arguing to focus only on product metrics. That’s too simplistic or idealistic because if you’re arguing this point, you’re really arguing that maximizing profits shouldn’t be the primary purpose of businesses. The issue with business metrics for product managers is it isn’t obvious what you should do next. It isn’t even clear where in the business you should investigate to figure out what to do next.

Secondly, business metrics don’t have to positively correlate with product metrics. Let’s modify the above situation.

End of quarter, gross revenue is $7.2MM. Awesome!

Now what? What action do you take to improve your product?

Many successful startups face this type of problem when growth and business metrics are great. You may wrongly be attributing that the product is working great! But then, when you hit a plateau or dip, you’re back to the same problem.

So, about these product metrics.

I define product metrics as measurements that determine how users are engaging with a product. Product metrics should help inform what changes to the product should be made. Some categories and examples.

Actions Metrics: Measures specific actions an user does with your product

users who convert by doing XYZ action (e.g., referral, click, search, share, watch, install, download, return)

how long users stay engaged (session length, page dwell time)

Errors Metrics: Measures when actions an user does fails to complete as expected

actions that fail to complete task

users who abandon/stop task (e.g., bounce rates, abandonment rate)

Performance Metrics: Measures how long it takes user or system to complete an action

time it takes user to perform XYZ action

time it takes for our product/service to do ABC before user can perform XYZ action

Product metrics are more granular than business metrics because product metrics measure users usage/engagement with the product. It doesn’t try to measure how well we’re able to get potential customers to be users (acquisition) or how well customer service is doing answer questions and concerns (customer service). [Note: I’m not saying these other areas of the functions aren’t integral to the product and outside your ownership. You can’t ignore them. However, it’s easy for product managers to get lost and start focusing on acquisition metrics or customer support metrics, if the first problem is the product itself.]

Framework for identifying the right metric

Identify your product goal and the difference with your business goal.

Whatsapp example:

product goal: “fast, simple, securing messaging and calling”. business goal: “user growth or monthly active users”

Understand your product strategy

Whatsapp example continue:

Early strategy: “get on more devices/platform”: Android, Blackberry, Symbian, Windows, browser

Then/Simultaneously: “more messaging features”: status notifications, sending pictures, deleting messages, emoji, encryption

After: “non-messaging features”: voice calls, video calls, group video calls

Brainstorm metrics based on your strategy

Whatsapp “get on more devices/platforms” example metrics:

engagement / week / segment: engagement is defined as some action that will drive repeat usage. Perhaps it’s sending your first message. Perhaps it’s defined as sending, receiving, and replying to a message. The goal is to make sure engagement isn’t defined just as signing up because of the product’s goal. Measuring this on a per week and adding different segments (e.g., based on persona, demographics, acquisition channels) can help inform if users are engaging with the product.

% of active users / platform: You’ve built it on more platforms and there’s a cost to support each platform. Measuring here tells you if you should still support the platform.

Whatsapp “non-messaging features” metrics:

% of video call that resulted in error/termination: Video calls can quickly turn into performance problems that quickly break the value of the product. A few experiences may turn a user to stop using this feature entirely. The same can be true of voice over IP. This is an example where a performance metric is often critical for a product.

Pick a few metrics to instrument and set targets

Now that you’ve brainstormed and ideated around some metrics, it time to pick a few. Here are some tips.

Easy to instrument > perfection. Defining a metric is just half the battle. You have to instrument it to collect the data, with the tools and then analyze it. Sometimes, you’ll come up with a metric that’s great, but perhaps really hard to instrument. For example, maybe you can’t get “activation / week / segment” because defining the segment logic is a lot more work. Then, it’s better to stick with “activation / week”. You’ve kept the measurement, and it can be updated later.

Set a target. People are often afraid to do this, but you need to set a target. The way to reduce the fear (which is fear of being wrong), is to write down how you arrived at the target. Yes, it’s a guess, but it should be an educated guess. If you’re afraid to set a target, know that others will either set one for you implicitly or explicitly and still assign you responsibility for missing the target.

Standardize, common > Custom, unique. Find out what metrics are commonly used in your type of business (ecommerce, SaaS, real estate) and try to see if you can use the same. This helps prevent re-inventing the wheel. In addition, you’ll eventually be compared against a competitor using a standard metric. If you do decide to create a unique metric, make sure you spend the time to standardize it across teams so everyone know how it’s measured.

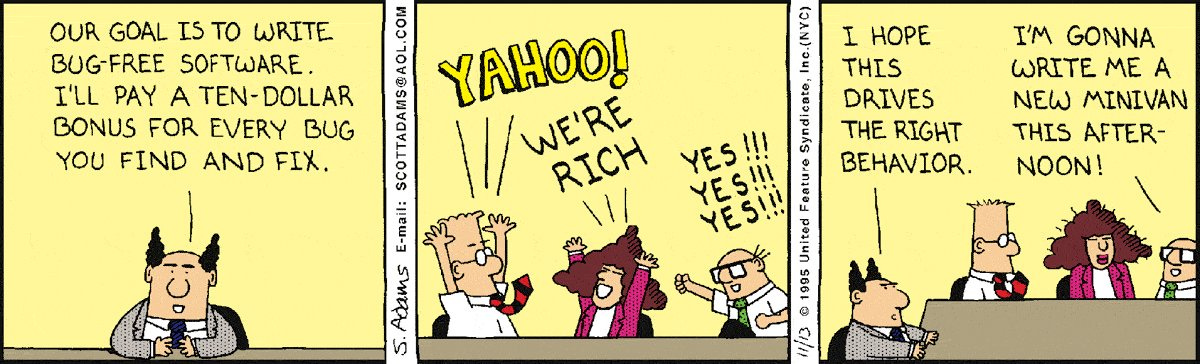

Think about how you might artificially intentionally manipulate the metric. All metrics, can be manipulated. Sometimes, people who are gaming the metrics don’t even know that they are doing it. To clarify, gaming isn’t when a technical accidentally occurs (e.g., counting something incorrectly). Going back to the Whatsapp, “activation/week” product metric. What if you kick off an incentive $5 dollars to anyone who signup for Whatsapp and send 3 messages? Are the users who you’ll count as activation/week the same as before the incentive? A different example: What if you change the onboarding process and introduce a tutorial that forces new users to sending 1 message? Again, this doesn’t mean you should drop your metric, but thinking about how the metric could be screwed around makes you mentally prepared.

Side Note: What’s up with vanity metrics? Do all metrics have to be actionable?

I believe no. But a Google search will tell you how everyone’s hates “vanity metrics”.

Vanity metrics are statistics that look positive, but don’t necessarily translate to any meaningful business results. Examples include quantity of social media followers or views on a promotional video. In reality, these numbers give you very little insight into how a product or initiative supports broader business objectives.

[Product Plan Glossary]

The “these numbers give you very little insight” statement isn’t entirely true. As the name implies, vanity metric focus upon vanity, but they give you some insight. We like to see lists of 100 riches people (even if we don’t know how they got rich). Companies like to talk about 100M monthly visitors (even if bounce rates are high)? It’s not that vanity metrics are bad, it’s that they may not help you in figuring out how to improve the product. But there are uses for them in getting publicity, building interest and momentum. Remember that reason and logic are not always the things people care about.

Sources: