The importance of defining product principles to guide product decisions

What are product principles and how to development them

As a product manager, you’re asked to make many decisions. All those decisions are mentally taxing and time consuming, especially when the choice is non-obvious, each requiring evaluation of its own benefits and costs.

To partly alleviate this taxing work, we can define and document product principles. The process of creating product principles and their application will help us govern our product, reducing the effort it takes to reach a decision. But what are product principles and how do you go about creating them?

What are principles?

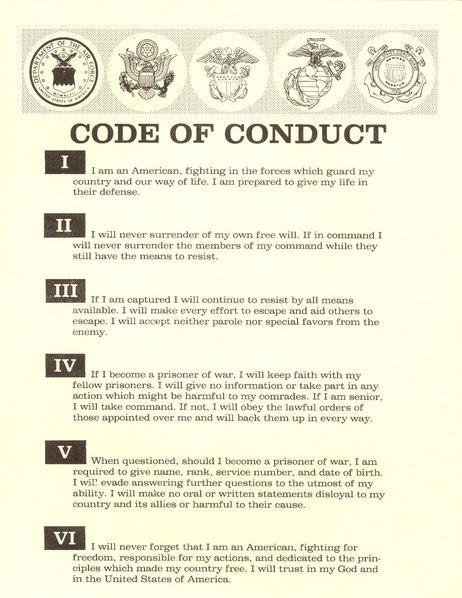

Webster defines principles as “a comprehensive and fundamental law, doctrine, or assumption; a rule or code of conduct.”

I like the “code of conduct” definition. A “code of conduct” can guides actions.

But what are codes of conduct when it comes to our product?

A few words on values and norms first, which are the precursor to principles.

Implicitly, values (what we believe in) and norms (shared understanding of what’s acceptable behavior) are all around us. For many startups with a single product, the product’s values and norms are intertwined with the company/founder(s) values and norms. Values might be “move fast, break things” or “win at all cost” or “do what’s best for the customer”. Corresponding norms might be “working late and on weekends” or “doing whatever it takes to succeed” or “going above and beyond to surprise and delight the customer”

I bring up values and norms briefly so you’re aware of where principles are derived.

Borrowing an example from John Rawl’s theory of justice to illustrate

Value: Ethical foundation of the “equality of all living persons”.

Norm: Derived from the value, is that “justice should prevail”

A Principle: There could be many, but one “example is the so-called

difference principle, the idea that inequality is only justified if it is to the advantage of those who are less well off.Choice: Application of the principle. “For instance, in property rights … stating that those rights should be established only as long as they benefit the poorest…”

Here’s an example if applied to product

Value: Accessible to all users

Norm: Enable anyone, anywhere, anytime, to use our product

A Principle: Features are only gated behind paywall if it doesn’t prohibit user access or the revenue collected can be used to support more free users

Choice: Don’t move a core feature behind a paywall only to increase revenue if it also results in decreased total users, including non-paying users

Not all principles are good.

If you google principles, you’ll get a bunch of what I term, fluffy words that are difficult or impossible to apply.

Let’s take a common principle I see used to describe a PM: “Be data driven”. On the surface, it doesn’t read as a bad principle. But let’s evaluate this phrase. What’s the opposite of this principle? “Don’t be data driven”, or “Don’t use data”, or “Make guesses about the data”?

Putting aside my snarky comment, the point is that many principles are written casually more as slogans without asking:

How would you put the principle in practice to guide a choice?

What’s the opposite of this principle?

Consider the alternative principle “Obtain two independently sources of data to support a decision”. This principle is more precise because it places restrictions.

Restrictions are good, the key to a principle.

You might read or hear some argue that a principles should be generic, inviting flexible implementation. I disagree, especially when it comes to product principles.

Recall that the purpose of these principles is to guide decisions. Take statement “Love our customers”. As a value, this is fine. Values are flexible. But as a principle, how would you put this into practice? Consider each of the options below.

Give new customers free access for a period of time

Randomly invite select customers to try out a feature

Reward customers for repeat usage

Each of these is an reasonable interpretations of the statement, but is one more appropriate than another? The problem is that our statement “Love our customers” is pretending to be a principle, but is actually a value.

It’s a value because it places no restrictions on our actions. Values have no restrictions which is why value words “clean design”, “universal appeal”, or “fast” are always positive. Value statements will always have positive appeal.

However, principles have restrictions that help with making trade-off decisions. The principle, “Double confirmation must be presented for any interaction where the user can’t undo their action” has trade-offs, such as speed. This principle will not be appropriate for all products.

Okay, enough with these points. What do I do if I want to create my product principles?

Write down a few value words about your product. These should all be positive words. Consider the value “Customers come first”.

Translate the values into principle statements. There are many different ways you could take to profess value. Perhaps: “Always do what the customer requests”

Evaluate the principle statement you made up. “What if only one customer demands a feature?”

Refine and refine some more:

Version 1: Initial: “What if only one customer demands a feature?”

Version 2: More specific: “Always meet customer demands if more than 5 customers request

Version 3: Try to generalize or reframe: “Always prioritize customer demands for the majority of customers over the minor.”

Consider the restriction and opposite restriction: “Always prioritize customer demands for the minority of customer over the majority”

Selection: Look through the various product principles and pick 4-5.

Stress test these principle statements against past product decisions. Do the principles guide you to the decision you’ve made? If so, good job (assuming those decisions are what you wish to repeat). If not, go back to step 4.

Iterate rather than dictate

The above is a reasonable process for defining and documenting product principles. But there’s an easier method. Consider that defining product principles is an iterative thinking process. You probably won’t get the correct principle the first time. It’s iterative because it’s unique to your values as the product manager (which are different than mine), but also unique to the values and norms of your company.

Thus, an alternative approach is to write down a few product decisions you recently made. The more contentious the better. Can you generalize how you arrived at your decision into a statement? In other words, what would you have told your past self that could have shortcut your evaluation to reach the same decision? That’s your initial product principle statement. Then, you can iterative on that statement by refining and considering the restrictions it’ll place.

Closing note: Product principle versus product manager principle

As you’re documenting product principles, it’s important to also evaluate if your principles are for the product or for the people working to create the product.

In many cases, we mix the two together. As I mentioned earlier, our product’s values and norms are often the company/founder’s personal values and norms. This means the principle you define might not be a product principle, but a “how people work” principle.

Recently, I encountered a “how we work principle” that we don’t release new software during certain time periods unless it’s a fix to address an active production issue impacting customers. This principle has explicit trade-offs, which some people will not agree. Those restrictions make this a principle that values stability during those time periods over change.

You want to avoid the later when creating product principles or at least be explicitly aware when you are writing principles for how people work. They are still principles, just not for product management decisions, but often product development decisions.

In summary

Principles are statements that can at as “code of conduct” to guide PMs in making product decisions

Developing your product principles is an iterative process, that you can start by writing down a few key words of what you value

Translating values into principles requires considering restrictions

Principles should restrict certain decisions, forcing a trade-off; otherwise, it can’t guide decision-making if the principle can have multiple, conflicting interpretations

When evaluating a statement for consideration as a product principle, devise the opposite principle as an evaluation technique

Recognize that product principles don’t have to guide how people work

Additional Reading

META-GOVERNANCE: VALUES, NORMS AND PRINCIPLES, AND THE MAKING OF HARD CHOICES (the paper’s introduction gives a good example of how principles are applicable to decision-making, it’s also where I pulled the diagram above)

Developing Design Principles (while this is about design principles, many of the examples are similar). However, be careful to stress test if the phrases are principles or values.