What characteristics make a good metric (with examples).

Picking the right metric is hard. But there is a systematic way to evaluate whether the metric you've ideated is a good.

Defining product metrics is difficult. While there are many frameworks (HEART, AARRR), deciding whether a metric is the good for your product requires understanding the framework, your product, and the product’s lifecycle. Learning the concepts doesn’t mean you necessarily know how to apply it correctly.

But there are a few guiding principles to help you evaluate each metric. Let’s review by looking studying some examples.

Guiding principles

1. Is the metric easy to understand and interpreted by people without training?

How do you know a metric is easy to understand and interpret? Take two metrics (NPS vs CSAT). NPS is Net Promoter Score. CSAT is Customer Satisfaction Score. Go around and randomly ask people what the metric tries to capture (assuming they don’t know anything). The better metric is the one where more people can define it in a similar manner.

In this example, customer satisfaction is easier to understand than net promoter. People intuitive interpret the customer satisfaction as how a customer would rate their happiness with a product. What does a promoter mean? Talking to a few different people and you’re likely to get different responses. Furthermore, the more complex calculation of NPS, which is % promoter - % detractors, makes the metric more difficult to interpret and thus understand without specialized training.

2. Will increases or decreases in the metric always have the same interpretation?

Let’s compare two metrics: Average page loading times per session versus Number of page views per session.

Average page loading time per session is a metric that is always better if it’s decreasing. While you might argue there’s no noticeable difference between 10 ms and 15 ms, a lower average page loading time per session is better than a higher. Always! Thus, increases or decreases are interpreted in the same way.

Compare this to Number of page views per session. Is more always better? Let’s try this with an example. Going from 2 page views per session to 3 pages views per session, you’d probably say yes. But what if you went from 2 pages views per session to 20000 page views per session? Assuming the metric isn’t broken, will your interpretation be the same (i.e., increasing in metric is always good).

You want to pick a metric that has a consistent interpretation as it increases or decreases. And this one is not always obvious without testing with hypothetical numbers. For example, I had to recently convince someone that “duration of call” is not a good metric for support agents because shorter calls isn’t always better (maybe the customer was so angry, they hung up), but neither is longer calls signaling of something bad. This is an example of a metric that is inconsistent in interpretation when it increases or decreases.

3. Is your metric a comparison (i.e., ratio or rate)?

Let’s compare two metrics: Page views versus page views per month.

Page views is not a comparison metric because there is no comparison. It’s a numerical count. But, we can take the metric and make it a comparison metric with page views per month.

First, we make it into a rate metric. You can consider different kinds of rates (e.g., per month, user, session, marketing channel, device, pages available). This allows you to compare over time (current versus prior) or with different groups (session type, device).

But be careful what you put in the denominator when making it into a comparison because some are in your control (e.g., marketing channel, pages available) whereas others aren’t (e.g., time). For the ones you control, you must watch for how the metric could be inadvertently changed. For example, if the metric is page views per pages available (e.g., 5 page views : 500 total pages) and I delete some old pages available (400 total pages), I would have inadvertently increased the rate.

4. Is it easy to measure and calculate?

Let’s compare website trust versus total one page visits per total website visits (i.e., bounce rate).

There’s research that says trust is a positive attribute, whether it’s customers trusting your product or coworkers trusting each other. But how do you measure whether someone trusts the content of your website? Is there a standard way to capture this measurement if you were to survey customers?

Compared trust to bounce rate. Bounce rate are easy to measure and not subjective. A user either only visits one page or multiple pages. Perhaps bounce rate can be a proxy metric for website trust? [Note: A proxy metric is an easier to measure metric than the intended metric. It’s questionable if this is a good proxy, but it could be.]

You want the metric to be easy to measure (data collection) and easy to calculate.

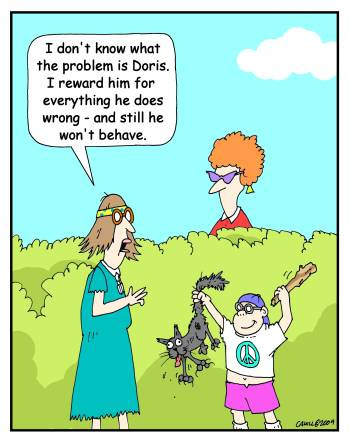

5. Does it drive the behaviors you want?

With the popularity of the Jobs to Be Done framework of focusing on tasks, it’s common to focus on reducing the time it takes a user to spend completing a task (i.e., average time spent on task). But if this is a metric, what behaviors might it drive in you as a product manager? What if you had to introduce a complex task? What if you needed to onboard new users? Would you consciously or subconsciously modify your behavior because this metric is being measured?

This guiding principle is probably the hardest to evaluate the metrics you’re considering. It’s not obvious how you or users might be manipulated by a metric.

To apply this principle, you can ask yourself a few questions:

How might you artificially inflate the metric, for better or worse?

If you had to suddenly make the metric look good in 24 hours to earn $100K bonus, what might you do?

Is there a way to cheat how the metric is calculated by including or omitting some data?

6. Do you have ≤ 7 metrics?

More metrics isn’t better. How do you know if you have too many? I use the magical number 7. Yes, you can go with one north star metric that rules them all, but one is sometimes not enough. So, if you need more, don’t go beyond 7 as a start. If you need to add more metrics afterwards, consider removing one of the original 7.

And those, are the guiding principles when you have a metric.

Additional reading

A Metrics Framework for Product Development in Software Startups (Literature Review)

Lean Analytics, Use Data to Build a Better Startup Faster