Why prioritization sometimes feels like art rather than science.

There is no art. There's only communication, both what is and isn't communicated.

My apologies for delaying the publication of this article. Last week, I was helping a friend who, unfortunately, was hit by a car. He’s recovering, thanks for asking. Life can throw curveballs.

A google search and you’ll find dozens of articles discussing prioritization. All those articles can be categorized into two camps. Camp one teaches a specific prioritization method, typically a numerical scorecard. That’s what I wrote in my previous article on RICE but you can find other prioritization scorecards such as Kano. Camp two discusses the “art” of prioritization, those things you can’t quantify into a spreadsheet.

When I started re-evaluating my prioritization templates (Prioritizing Work and Prioritization Framework Template (RICE), I wanted to first think beyond the templates. Yes, the templates could be better, but was there more? This led me to re-evaluate the concept of “art” in prioritization. What does “art” mean? Is there art in prioritization?

Prioritization is easy if everyone can agree can prioritize using the same prioritization process.

I dislike the phrase “art and science.” Writers frequently use it to describe prioritization.

I dislike the phrase because I find it ambiguous and disingenuous, specifically the word art. When contrasted with science, art signals the non-qualifiable, the soft skills the unspoken nodes, what is implied, or the magic dust.

Those who are “good” or successful at prioritization must thus possess this difficult to understand and pinpoint skill. But I want to challenge the premise: Is there art in prioritization?

How prioritization is conducted signals how decisions are made.

Prioritization is a fancier word for describing how we decide what individuals or teams should do. Thus, for prioritizing product work, we can examine how decisions are made.

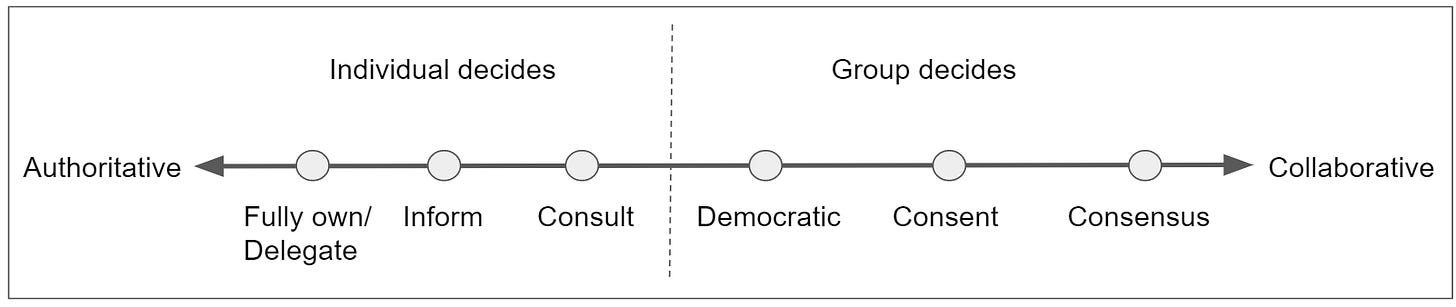

Decision making falls on a spectrum.

Different people and companies fall on different parts of the spectrum. For example, you might be in Group Decides via consensus, but you wish to be at Individual Decides via inform (or vice versa). The engineer you work with might have a different perspective. Your CEO another. Multiply the different perspectives among people working together and confusion or conflict naturally follows when people don’t know or agree upon prior how decisions should be made.

Thus, I believe the “art” that we attribute to prioritization is the ability to navigate these different decision-making perspectives, successfully, without fixing the root cause of these differences. Essentially, people who are good at applying art are able to sense and navigate these differing perspectives.

Navigating these differences is an “art”

Let’s consider a very simple prioritization scorecard: value versus effort.

Conceptually, easy to explain and use. But let’s consider the Y-axis: value. When we write value, value to whom?

Ideally, you answered, the customer. But is this always the answer?

For B2B, the customer might be separated by user versus buyer. What if it’s valuable to the buyer but not the user?

What if it’s valuable to a partner or supplier, but not the customer?

What if it’s valuable to a board member, but not the customer?

What if it’s valuable to your boss, a feature key to a promotion?

What if it’s valuable to a particular individual, perhaps an engineer to try some new tech package?

The point is, value to whom? As we each prioritize or judge how others prioritize different problems or features, we are applying these different perspectives. Now, there are three problems:

Some people aren’t aware of their perspectives.

Some people are aware, but can’t communicate their perspectives

Some people are aware, but don’t want to communicate their perspectives.

Why art is a band aid.

Take a situation you might have experienced.

The product team meets, prioritizes various problems that it can try to tackle.

Afterward, it proposes two problems to focus upon as having the highest potential to drive value.

Solutions are brainstormed and again, solutions are also prioritized, based on value versus effort.

All the above takes at least week, not including time to communicate the decisions and implications to people outside the product team.

As the team starts the project on the first solution, the CEO instructs the PM and product team to focus on a new, urgent problem.

From people inside the product team, the change will usually feel chaotic. This is partly because a group of people usually uses the Group Decides - democratic method. From the CEO’s perspective, it was last minute, but not chaotic. The CEO was using the Individual Decides - inform method. The CEO might even take the extra effort to explain his or her rationale for the last-minute request. These are usually in the form of “a call to urgency”. One prominent example playing out is Elon’s class of Twitter potentially going bankrupt.

In any case, the art attributed to prioritization process is the PM’s ability to navigate these sudden changes, not only in terms of project work, but primarily to make members of the product team feel they are emotionally bought into whatever is the new direction.

I view this art acting like a band aid on a wound. It doesn’t solve the core problem, which is that someone or something entirely disrupted the prioritized results. This core problem can’t ever be solved just as you can’t solve that sometimes it’ll rain.

What you can try to do is:

Foresee changes and communicate likely changes.

Understand the rationale for the last-minute change when it occurs. In these situations, be mindful of what is and isn’t communicate as the rationale for the new request.

Make leaders aware, that frequent last changes that are directives, require recovery before you can make another last-minute request.

Revert back to the agreed upon prioritization method as soon as the urgent change is over.

In summary

Pick a prioritization method.

Define how you will make decisions using that prioritization method

Expect periodic last-minute request that may supersede the prioritized results, but understand why in terms of what is and isn’t communicated with the last minute change.

Apply the band aid with the product team when communicating the change, but also communicate to leaders that a recovery period is necessary before another last-minute request.

Thank you to all my readers. I thought briefly about writing more on “foreseeing changes” as the art, but I don’t believe there is a concrete method to teach forecasting, which is situation dependent.

Additional Readings

First Things First: Prioritizing Requirements (A paper from 1999 that had a scorecard for prioritizing for value, illustrating that scorecard is an established technique)

I love this article, this is exactly what I come across and sometimes it's difficult to prioritize as it depends on who is taking the decision. I liked the Decision Making illustration. I think the more you understand the prioritization decision owner the more you know if we are going on the right path towards our vision and goal. More Collaborative decision-making makes it more reliable for achieving not only our goals but goals for the organization. Obviously depending on the company and role you are on, decision-making varies but our goals should be to make it more collaborative